Please read Frans de Waal’s op-ed in the recent NYT entitled, “What I learned from tickling chimpanzees.” Link: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/10/opinion/sunday/what-i-learned-from-tickling-apes.html?action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=opinion-c-col-right-region®ion=opinion-c-col-right-region&WT.nav=opinion-c-col-right-region&_r=0

It is a brilliant and clear statement of how many scientists and others think wrongly about our own species and how we can go about understanding our place in the biological world more fully. Ah, this is a subject dear to my heart, not just that humans are animals but our thinking, religion, culture, art, science, etc. are all products of our biology. Two of his points are most memorable at the first read (but read all of it, not that long and full of insight). One is that we continue to follow Aristotle’s classification of higher and lower animals and of course you can guess which animal is on top. Western religion adopted this wholesale in the great chain of being, if you took and remember some English literature classes, where God appoints the pope, king and nobles and then each class in its turn. Anyone who rebels against his ‘place’ is guilty of breaking the great chain. Learning from Darwin and evolutionary genetics we understand that there is no chain but rather many streams of genetic speciation, some similar, some related, some both, and some quite divergent. He says it better.

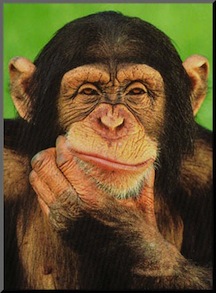

The other memorable point is his explanation of the proper place of anthropomorphic thinking. Many scientists are phobic of using words normally used for humans to label the behaviors of other animals, thus the ‘tickling’ chimpanzees which results in laughter (you know, the positive affectively charged hooting with lips retracted but not showing teeth). Of course folk wisdom and culture attributes many human attributes to animals, e.g., cats are aloof, dogs feel guilt, horses paint artistic pictures, etc. but the misuse of such attributions is no reason to deny the continuity of abilities and functions across species, including us. Yes, birds and humans do sing, their songs differ in many regards yet are similar in others and we can learn about music from understanding these biological roots. De Waal offers another term ‘anthropodenial’ to denote the refusal of some to recognize our commonalities—read what he has to say.

I have written several times about what I have read in 2 of de Waal’s books, The Bonobo and the Atheist and The Age of Empathy. One story from my post on March 9, 2015 “Memory and regret”, de Waal tells of a bonobo that accidentally bit off the finger of scientist-caretaker and immediately showed all the signs of realizing his transgression. When that worker returned for a visit some years later after taking another job, the bonobo ran to the window in greeting and recognition and kept trying to gain a view of the hand he had bitten. To deny he remembered his action and felt bad about it would violate empirical observation. My question back then, unanswerable without engaging in symbolic communication with the bonobo, was if the bonobo over the years had recalled, not just recognized, his misdeed, say in a reflective moment or falling asleep or waking with insomnia, the memory held invariantly through guilt as we humans are wont to do, or only remembered in recognition of the worker and the associated memory based upon the mechanisms of recognition. A big difference.

Well, that is certainly a mystery to me too.

I will say more about this in a few days as I begin my discussion of Ellen Dissanayake’s book Homo Aestheticus, which opens making just the point de Waals makes, that humans are distinct and have special abilities, as do every other species, and that these have common biological roots in our evolutionary past. Our notion of human exceptionalism misleads us from a better understanding, in her instance of art. For now though, read Dr. de Waal’s piece. He is one of my champions and I say once again, “Thank you.”