I am going out on a lark here. I just read an excellent review of research along with a proposed model of how our brains do empathy: “A social cognitive neuroscience model of human empathy” by Jean Decety in another great collection of papers, Social Neuroscience: integrating Biological and Psychological Explanations of Social Behavior. We are going to go into some complexities here but in truth, the reality is even more mind-boggling. So Dr. Decety postulates 4 components to empathy:

- ‘Shared neural representations’ which I understand to be the mirrored actions, especially emotional expressions, by which we resonate with one another. (See posts 9/27/15, 7/29/15 & 7/31/15).

- ‘Self-awareness’ which I take to be essential in knowing which resonant activity originated within us and which within the other.

- ‘mental flexibiity’ by which Decety means the ability to set mentally one’s own perspective in the background and so enable the taking of another’s perspective.

- ‘Emotional regulation’ which I understand to be quite basic to developing empathy and also higher intellectual skills. The development of emotional regulation is critical to our maintaining focus on our current mental set, intention, and task as well as to setting our personal feelings aside to address the concerns of others.

As Decety explains these 4 components, he reviews the neuroscience, including clinical findings, relevant to each. For example, autistic people can generally engage in mimicry, i.e., mirroring, intentionally, but do not do so incidentally and this latter is necessary for mentalizing about another’s state of mind. It is one reason researchers like Ramachandran and Baron-Cohen (see my post 7/29/18 ) think autists suffer from a mirroring deficit.

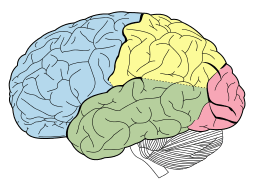

The neuroanatomy supporting empathy is also profoundly complex. Generally there are centers in the posterior brain, especially in the right hemisphere, that receive and integrate social information, and centers in the front of the brain that provide executive functions and guided responses to that information, again especially on the right side. The front and back areas communicate with each other directly in some cases through long fasciculi, i.e., nerve fibers traversing the cortex, and also through their interconnections with lower centers like the hippocampus for memory and limbic system for emotional processing.

Exterior view of left hemisphere. Lobes are same on the right. Some structures are deeper within the larger folds.

Decety does an admirable job sorting through various findings to present relevant hypotheses about neural functioning. For example,

- The frontal polar cortex facilitates inhibiting our own perspective, which is the default one that we usually follow in our considerations, in order to take on another’s perspective. This area also helps evaluate our own responses and behaviors for their contextual fitness, i.e., do they fulfill the intent? Was the intent properly developed from a coherent adequately formulated context?

- The prefrontal cortex interacting with the inferior parietal lobe (in the back and integrating information from many perceptual sources) and the insula (old cortex deep with the brain kind of in the middle) on the right side helps to differentiate actions from one’s own self from those of another.

- The paracingulate sulcus (again old cortical structures deep in the brain) in the medial prefrontal cortex helps process social feedback, i.e., how do others view our actions?

And so forth. I always find it amazing to consider that while these areas are performing these particular functions, they are also contributing to many others, e.g., attention and focus, memory input and output, etc.

Two ideas here struck me as particularly interesting. First, damage from say a stroke to the right frontal lobe so important to emotional expression and social responding sometimes shows up in personal confabulation, i.e., the patient makes up stories about themselves seemingly unaware that he is doing so. The second is that when faced with the personal distress of others, say due to their own circumstances or even to their assessment feedback of the original actor’s actions in some matter, our brains can respond either with empathic concern given their perspective (an optimal response) or with egoistic anxiety (retreating to one’s own narcissistic concerns).

Well, we have covered a good deal of ground here. In my past life as a clinical psychologist I worked with many youth, including some with attachment and sexual aggression problems, who had deficits in some of these empathy ‘components’. Each person’s deficits were unique in form and history and most retained some islands of empathic functioning. Let me list some major areas:

- Failure to resonate with another. The person may only resonate when the other mirrors them, but they seem unable to mirror or resonate with the other’s feelings.

- Confusion as to the agent of thoughts and feelings. They think their own thoughts and feelings are also the other’s and they may fail to process accurately social feedback when the other tries to disagree or otherwise present their own perspective.

- This leads to problems with perspective taking. They may assume that their perspective is shared by everyone.

- Poorly developed emotional regulation presents difficulties for staying on mental task and intent as well as for responding with empathic concern for the other—instead they act upon their own egoistic anxiety and fail to engage socially in an adequate manner.

As I read and thought about these ideas I kept thinking of someone who seems to experience all of these deficits despite what otherwise may be intact intellectual capacity. And I wondered if scientists could study that person’s neurological structure and functioning to learn from what seems to be an unusual case, someone whose empathy deficits appear global but without a history of neurological disease or injury or of developmental trauma. I can think of only one person like this at the moment and that is why I want to ask our President, Mr. Trump, to donate his brain to science upon his death. I know more could be discovered if he were to undergo evaluation while alive through experimental protocols, e.g., using fMRI, but I also know he is much too busy being president and running his businesses to do such a thing. I am not talking about a simple post mortem autopsy such as the one that found a tumor impacting the amygdala of Charles Whitman, the Texas tower shooter (see my posts 9/3/15 & 12/26/17), but a detailed scientific examination of his brain structure, sort of like we wish would have happened with Einstein’s brain, which unfortunately was not done very rigorously. I believe a knowledgeable neuroanatomist could assess the integrity of most of the relevant areas and some of their interconnections.

Now I have no way really of getting my message to our President and I am not on Twitter nor knowledgeable about it, but I wonder if some tweeting aficionados sent out some messages using #SaveTrump’sbrainforscience (if I understand the format correctly), what might transpire. Travel on.